Following the end of the Civil War, the IRA would be forced into an underground campaign by the Free State. They would remain relevant in the North of Ireland and in border communities but, most of their membership would consist of people from the South. In the antebellum period between the Irish Civil War and the beginning of the Troubles in 1969, the IRA would launch three major campaigns against the British government in the North. The first was known as the Sabotage or England Campaign. This lasted from 1939 to 1940 and mainly consisted of attacks on the British mainland. The plans for the campaign designated two distinct kinds of actions: propaganda and offensive. Propaganda actions were meant to gain support for the IRA and be used as a trophy achievement. Offensive actions were those targeting key military and civil infrastructure in Britain. These plans were not always followed, with many of the attacks taking place in civilian areas. Needless to say, the campaign was a failure for the IRA. In fact it is often said that the plan itself was harmful to the IRA, its reputation, and the Irish people as a whole. As a result of these attacks, anti-Irish sentiment increased in Britain. The campaign was reminiscent of the Fenian dynamite campaign of the late 1800s, headed by Irish republican legend Jeremiah O’Donovan-Rossa. That campaign also failed to achieve any real success. The Sabotage Campaign was even seen as a failure by the main creator, Seamus O’Donovan. O’Donovan stated in his journal in August of 1939:

“hastily conceived, scheduled to a premature start, with ill-equipped and inadequately-trained personnel, too few men and too little money…. ..unable to sustain the vital spark of what must be confessed to have fizzled out like a damp and inglorious squib”

This was at the height of the campaign and showed that the IRA Army Council was not very prepared and stuck in the Irish republican tradition. This period of IRA history leading up to the Troubles is seen as a period where the IRA was alienated from the Irish people and did not maintain the people’s army status that had been seen during the Tan War and Civil War. The IRA was also flat-out reactionary during this period. The Sabotage Campaign had begun a relationship between the IRA and the Abwehr, the Nazi foreign intelligence service. The history of IRA-Abwehr collaboration is both a dark and interesting one. Many historians ask as to why the IRA chose to collaborate with the Abwehr. Most tend to believe that it was mainly a form of realpolitik on the part of the IRA. This meaning that the IRA did not really agree with the agenda of the Nazis but, rather, were using Nazi aid as means to an end. This idea was probably also somewhat spurred by the example of Subhas Chandra Bose in India who had been promised Indian independence by the Nazis. Needless to say, it is hardly acceptable and collaboration with fascism is a terrible thing. This only damaged the image of the IRA during this period.

The next two major IRA campaigns were the Northern Campaign from 1942-1944 and the Border Campaign from 1956-1962. The Northern Campaign is a product of IRA confidence in Abwehr support. It was a fairly low-level campaign that consisted of attacks on RUC barracks, Free State barracks, and other targets. The campaign was a total and complete disaster for the IRA. By the end of the campaign, IRA activity in Northern Ireland had to cease due to the pressure of the British government. The Border Campaign of the 1950s and 1960s is viewed as a mixed bag. While tactically a failure, it is seen as the main reason for the resurgence of the IRA in a new generation. Despite this “resurgence”, the IRA still remained weak throughout most of the 1960s. It would not regain prominence until the beginning of the Troubles in 1969. The IRA was lacking in arms and popular support throughout the majority of Ireland. The support was only maintained in small communities in the North and some moderate political support in the South. Even with the support of the small communities in the North, the mainly South-based command and Sinn Fein leadership became alienated from the people in the North. This became truly apparent when the Northern Irish Civil Rights Movement came about in the 1960s. While the IRA was failing in many ways, the socialists and Marxists of Ireland were seeing varied success.

The socialist movement in Ireland was strengthened by the combined sentiments of the martyrdom of James Connolly and the success of the October Socialist Revolution in Russia. The Irish Transport and General Workers Union would continue to exist well into the 1990s before a merger with the Federated Workers’ Union forming the SIPTU. Besides this, the Irish socialist movement in the antebellum period would be somewhat fractured and ineffective. While the IRA was maintaining a broad, bourgeois nationalist position, working people did not stop joining. Much of the ranks of the IRA during both the Northern and Border campaigns were working-class Irish farmers. Most famous of these would be Frank Ryan, a socialist republican and member of the communist Republican Congress. It was the Republican Congress that would also boost efforts in the 1930s for volunteers to fight in the Spanish Civil War. The experiences of the Connolly Column and those Irish men and women that fought for freedom in Spain could constitute a whole book of heroism and, sadly, cannot be done justice in such a small space. What must be taken from the drive for Irish volunteers in Spain is the increase in left-wing elements beginning to sprout in Irish Republicanism. This is a major development because, while both the socialist and republican movements shared the same origins in the Easter Rising, they had developed semi-independent of each other. Both were relatively unsuccessful but, the republican movement saw the greater broad appeal to the masses and since socialists in Ireland tended to also agree with republican sentiments on national liberation, the movements morphed into one. This morphing of the movements greatly increased the ability of both socialists and Republicans to get their messages out to a broader range of people. Republicans were able to use the trade unions more to persuade more working class people to join up with the IRA and socialists were able to use Sinn Fein’s appeal in the countryside and in the North to gain more support for workers’ movements in Ireland. This morphing also led to the post-Border Campaign Marxist takeover of Sinn Fein and IRA leadership. Under the leadership of Cathal Goulding, the IRA and Sinn Fein began to make radical changes to their tactics. Goulding and the leadership looked at the military failures of the Border and Northern Campaigns and attempted to synthesise a new method for carrying out the struggle. This new method was to follow the Marxist-Leninist line (at the time) that the struggle in Ireland was merely a bourgeois nationalist struggle and that the only way to truly achieve freedom in Ireland is to maintain a working class line to unite all people. This sounds good when said out loud but, it ignores the fundamental conditions in Ireland, the situation in the North, and the present threats of the British. By this point also, the struggle and the IRA were mainly centred in the Occupied Six Counties of Ulster and Belfast. Even though they were centred there, the IRA would still not see much support throughout most of the 1960s. The late 1960s would begin the new rise of the IRA as the Troubles would begin in Northern Ireland.

Understanding the Troubles in Northern Ireland is key to understanding the modern Irish struggle. It is the most important event in recent Irish history as it has done much to determine the shape of Irish politics, international politics, international socialism, and much more. The Troubles is also an infinitely complex topic that can sometimes be hard to represent in a clear and understandable way. So, try to excuse any vagaries that may come about. The generally accepted year for the start of the Troubles is 1969 when the Official IRA began its armed campaign but, the origins of the Troubles extend farther back. In 1922 following the signing of the Anglo-Irish Treaty and the official partition of Ireland, the British government passed several laws to try and repress Irish republican sentiment in Northern Ireland. The most atrocious of these laws was the Special Powers Act, this act allowed for police to stop and search anyone they pleased, this mostly referred to Irish Catholics. Discrimination was also rampant in Northern Ireland. The Protestant majority was treated far better than the Catholic minority, with Catholics finding it impossible to find jobs and housing in non-Catholic areas. This led to a massive homelessness and unemployment problem within Catholic communities. Catholic communities in Belfast and Derry were also subject to raids and attacks from both the Royal Ulster Constabulary (RUC) and gangs of Unionists. This culminated in the formation of the Northern Irish Civil Rights Movement, inspired by the American Civil Rights Movement of the same era. This movement culminated in the formation of the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association (NICRA), the largest and most important of the organisations, in 1967. This movement would see the rise of many prominent politicians such as Gerry Adams, John Hume, and Martin McGuinness. The NICRA established what became known as the 5 Aims and 6 Demands which were:

5 Aims:

- To defend the basic freedoms of all citizens.

- To protect the rights of the individual.

- To highlight all possible abuses of power.

- To demand guarantees for freedom of speech, assembly and association.

- To inform the public of their lawful rights.

6 Demands:

- One man, one vote

- An end to gerrymandering electoral wards to produce an artificial unionist majority.

- Prevention of discrimination in the allocation of government jobs.

- Prevention of discrimination in the allocation of council housing.

- The removal of the Special Powers Act.

- The disbandment of the almost entirely Protestant Ulster Special Constabulary (B Specials).

These would become the backbone of the movement and would also be the rallying cry for Sinn Fein and Republicans when trying to garner support. The success of the NICRA and Civil Rights Movement would provoke a strong reaction from the British government and the Protestant unionist population. During civil rights marches, RUC and B-Specials would charge at the crowds with batons and beat protestors to within an inch of their lives, sometimes they would kill them. Gangs of unionists would also attack marches and rallies with firebombs and blunt weapons. These attacks on rallies would escalate into reprisal attacks on the Catholic population itself, with homes and schools becoming the primary targets of RUC and gang attacks. The Catholic population was left defenceless against the onslaught, so they began to defend themselves. Many began to come to the protests with hurling sticks and blunt objects to fight off the RUC and unionists, this led to the further escalation of sectarian violence but, it was a justified reaction. Inter-community attacks became more and more violent and the IRA was also at the beginning of its reemergence so, after the O’Neil administration in Northern Ireland failed to stop any of the protests, Westminster declared direct rule and sent in the British Army. Thus began the Troubles.

At first, the British Army was looked upon positively by much of the civilian population, Catholic and Protestant, for they saw them as peacekeepers. This would not last when the August Riots of 1969 broke out in Derry. RUC officers had beat an innocent Catholic man to death in his home, leading to protests in the Bogside area of Derry. These protests escalated into rioting with the Bogside being almost inaccessible by the end of it. Eight people died with another 700 injured. It was a disaster and was seen as the first true escalation of the Troubles. In response to this paramilitary groups would begin to fill the void for community defence. The Official IRA saw a massive resurgence and began to institute the armed struggle against the British in 1969. The loyalists formed several paramilitary groups, most prominent are the Ulster Volunteer Force (UVF) and the Ulster Defence Association (UDA). Both of these groups were full of bigotry and hatred towards the Irish Catholic population and deserve the title of death squads, given much of their actions. The IRA, however, began to gain people’s army status. In the early 1970s, the IRA proved itself effective during the Battle of the Bogside where the people of Derry declared the area a free zone, free from British incursion. They would call it “Free Derry”. The Free Derry sign is one of the most iconic symbols of the Irish struggle to this day. The gallant example of the fighters in Free Derry would inspire many Irish people to join the IRA but, even with this success, the IRA was still having internal problems.

The IRA was facing struggles between the leadership, which was more Marxist, and the traditional Republicans. This feud was exacerbated by the IRA backing down on defending Irish Catholic communities in Northern Ireland, an essential function it had performed since the 1920s. Even with this, the IRA somehow stayed together but, it would not last. In 1972, one of the worst attacks of the Troubles occurred in Derry. This was Bloody Sunday. The attack was at a protest done by the NICRA against the British policy of internment without trial (known as simply internment). The British Army’s 1st Battalion, Parachute Regiment, a battalion known for brutality, opened fire on the protestors killing 14 and shooting 28 overall. This attack sparked fierce outrage amongst the people of Ireland and they demanded a response. The IRA, however, would prove to be ineffective in dealing with the issue. Later that year the IRA would declare a ceasefire with the British, at the height of the Troubles with loyalist attacks still rampant. For the sensible factions of the IRA, this would be the last straw. The largest grouping left the Official IRA and formed the Provisional IRA (PIRA), nicknamed the Provos. The PIRA would become the most prominent Republican group in the struggle, controlling the mainstream Sinn Fein and garnering the most public support. The PIRA were not the only people in the split, however. Other Marxists who realised the reality of the material conditions in Ireland would also leave the OIRA to form the Irish National Liberation Army (INLA). They would be headed by Seamus Costello and would maintain a fairly large support base and cooperate with the PIRA most of the time. Seamus Costello had the correct line on the situation in Northern Ireland. He realised that, yes technically the struggle in Ireland is a bourgeois nationalist one but, according to Lenin’s theory on self-determination, it is sometimes necessary to work within those confines in order to achieve socialism. Costello was also aware that allowing working people to be killed by loyalists and the British Army was counter-productive. The INLA became focused on fighting the British but, their success would not last. Costello was murdered by an OIRA gunman on the 5 October 1977, this ended much of the success for the INLA as they had lost their central figure.

The campaign of the PIRA would only escalate throughout the 1970s. Increased frequency of bombings and campaigns would effectively begin to weaken the British grip, somewhat. It has been said by revolutionaries that, just as the reactionary is about to die, it fights with greater ferocity. Ireland proves this point entirely. The British clamped down harder on the IRA and the Catholic population. Internment was heavily enforced leading to many prominent IRA and Sinn Fein members being imprisoned. These prisoners, however, did enjoy a special status within British prisons in Northern Ireland. This so-called “Special Category Status” treated IRA prisoners more as POWs than criminals and it was an odd act of leniency for the British. It would end in 1976 and most IRA prisoners would be sent to the H-Blocks of the Long Kesh Prison. It was in the H-Blocks that many of the prison abuses of the British would happen. There were beatings, humiliation, and near concentration camp conditions imposed on the prisoners. This coupled with the loss of special category status would lead to protests that would culminate in the 1980s with the hunger strikes.

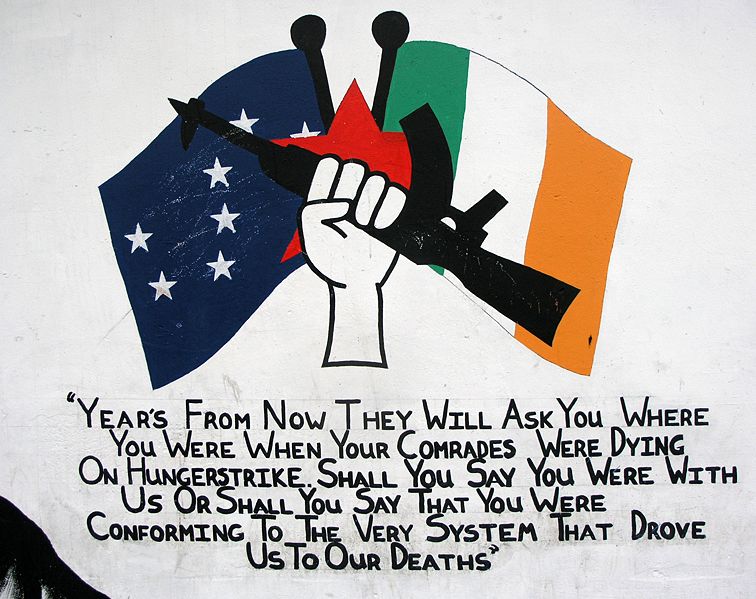

The roots of the hunger strike go back to 1976 when Special Category Status was originally revoked. Many of the new prisoners refused to wear prison clothes and wore blankets instead, as a symbol of defiance. This escalated when prisoners were attacked by guards in 1978 to a “dirty protest”. Dirty protests are when prisoners coat the walls of prison cells in human waste. This still was met by no response by the British government. In 1980 the first hunger strike occurred in Long Kesh with 7 people participating. This ended after 53 days due to a notion that the British were going to give in, they were wrong. The British government under Margaret Thatcher were never going to give in to the IRA unless something drastic happened, and that would occur in 1981. The second hunger strike began on 1 March, started by Bobby Sands. Bobby Sands would valiantly lead 23 other volunteers on the strike, 10 would end up dying before the end of it. Their sacrifice would be immortalised in the republican movement, despite the rocky start in the beginning. The hunger strike would become an international event. People from all over the world poured support for the hunger strikers and as each died, the outrage towards the British government grew. One of the most brilliant and inspiring moves of Sinn Fein during the hunger strike was the usage of Bobby Sands as a candidate for parliament. This garnered great amounts of support for the hunger strike and was even more inspiring when Sands won the election. Sinn Fein was able to do this by using a loophole in British law that allowed people in prison to still technically run for parliament. They also got around the ban of Sinn Fein by using a front party called the Anti-H Block Party. The strike was called off on 3 October and the British would restore Special Category Status to the prisoners in all but name. The hunger strike is considered a success in both a tactical and political sense. It achieved human rights for the IRA prisoners in prisons and also boosted Sinn Fein into international prominence. It would also show a willingness on the part of the British to compromise with the IRA, this would lead to a sharp change in tactics.

The 1980s proved to be a decade of both military and political success for the IRA and Sinn Fein. The hunger strike of 1981 garnered international support and a willingness of the British government to compromise on certain issues. One other issue came up, abstentionism. Abstentionism had long been a policy for Sinn Fein. It essentially means that Sinn Fein would not seat representatives in the British parliament or the Irish parliament. This is due to a concept known as Irish Republican Legitimism. Legitimists believe that the only Irish government was the one proclaimed in 1916 and the only official body of that government was the IRA Army Council. To Gerry Adams and other Sinn Fein leadership, this seemed like an unproductive policy given the electoral success of Sinn Fein during the hunger strike. This issue would come to a head in the 1986 Ard Fheis when it was decided that Sinn Fein would put up candidates for election to the parliament in Dublin but, would still maintain abstention to the British parliament. This new policy would be termed “Armalite and Ballot Box” as it was a synthesis between electoral politics and the armed struggle, realising the need of both in the Irish struggle. Some of the traditional republicans did not agree with this and left the Ard Fheis to form a new party called Republican Sinn Fein, they have been relegated to irrelevance for most of their existence and represent a more socially conservative section of Irish republicanism that is not popular in Ireland today. Armalite and Ballot Box boosted Sinn Fein’s position in politics, giving them more legitimacy with the British and internationally. With this, the IRA still continued the armed struggle, haranguing the British at every chance. As the 1980s came to a close the struggle had stagnated somewhat in its general activity. IRA actions were regular but, were also being met by an equally strong British reaction. The population of Northern Ireland was also beginning to become tired of this after almost 30 years of fighting. The time for peace was coming.

The beginning of the 1990s saw an increase in IRA activity, with more attacks in Britain trying to hit close to home and pressure the government. The mid-1990s would see the beginning of peace talks between Sinn Fein led by Gerry Adams and Martin McGuinness, the SDLP led by John Hume, and the DUP headed by preacher and bigot Rev. Ian Paisley. These talks would start off rocky, to say the least. The IRA ceasefire of 1994 broke down after loyalist attacks on Catholic communities increased. The talks between Sinn Fein and the government also began to break down after a lack of compromise on the part of the government. The talks between political parties maintained a cold feeling as little to no progress was made. It was looking hopeless and Sinn Fein knew this. Sinn Fein did not want to compromise on a United Ireland but, as the struggle brutally continued, Sinn Fein capitulated to the British in 1997. 1997 began the resumption of dialogue between the political parties to form a new government in Northern Ireland. In 1998 a final agreement was signed, known as the Good Friday Agreement. This agreement brought peace but, still maintained the partition of Ireland. The RUC was disbanded and the new Police Service of Northern Ireland (PSNI) was established. Systems and organisations to protect and promote the Irish language were also set up. The Agreement did all in its power to try and maintain peace for as long as possible and the lasting effects of it still remain to be seen 20 years on. Low-level dissident republican violence continues to this day but, has been dying down in recent years. These dissident groups lack the popular support the PIRA had to be able to carry out such a large armed struggle. As of now, Ireland is at peace, albeit a strained one, but, that is what matters to the Irish people as of right now and the will of the people is what truly matters.

The Troubles have a lot to teach us about the nature of both the Irish situation and general struggles for national liberation. It is a shame that this is not able to cover every detail of it and I highly recommend you read about it more in depth. But, what should we take from the Troubles? Well, while for many and me personally the acceptance of partition is a betrayal of the Irish people, peace is more desirable than bloodshed after 30 years of the latter. The struggle continues in its own ways and will always continue for as long as it needs to. What we should also take from the Troubles are the courageous examples of revolutionaries and freedom fighters that died fighting for the freedom of their people. The struggle in Ireland was one recognised by revolutionaries such as Fidel Castro and Nelson Mandela as noble. The IRA maintained mutual solidarity with the people of Palestine whose struggle is very similar. If you take one thing from the Irish struggle it should be this: Never give up.

The Irish people throughout history have remained resilient and steadfast in the struggle and I hope that I have shown that. I also hope that fellow Marxists and socialists learn something from this and the further research they will do into it. Irish history has a lot to teach us and should not be shrugged off. In conclusion, to quote Irish revolutionary Padraic Pearse:

Ireland unfree, shall never be at peace

…..

I do hope the few of you who read this blog enjoyed this small series of posts. It was very fun for me to write and research as it is something I am passionate about. I would like to apologise for the brevity of this essay in some parts. The Troubles are a very complex topic and to go over every single event would take a lifetime. If you feel I missed anything important or have questions feel free to contact me!